Why Prediction Markets Are Where They Are

Traditional betting platforms will still surpass on-chain betting platforms but that leaves the question of why and how, and how long?

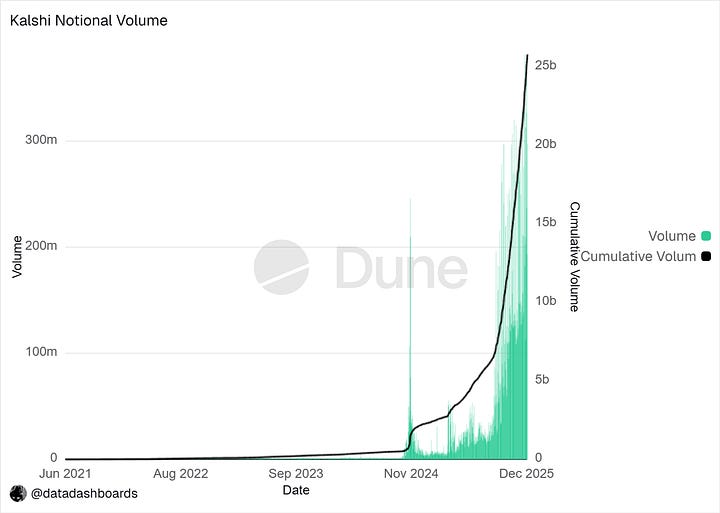

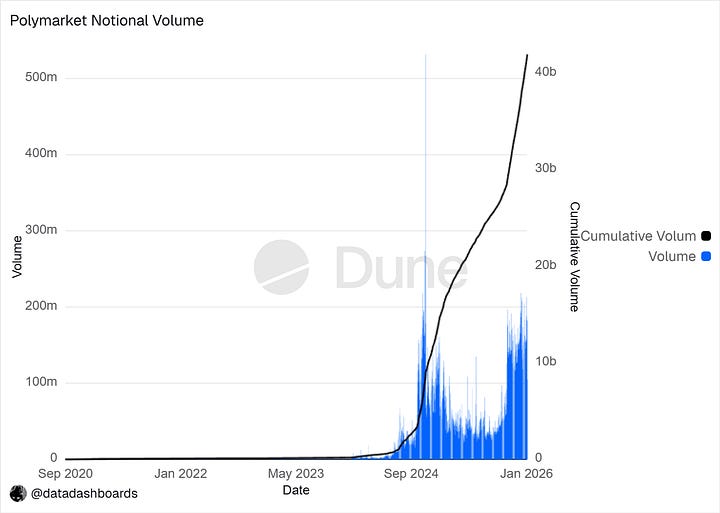

Polymarket and Kalshi have recorded over $41B and $25B in notional volume, respectively, figures that far exceed those of other prediction market platforms.

Since the U.S. elections, Polymarket, while indirectly creating room for Kalshi’s growth, has attracted significant attention both within and outside Crypto Twitter. This attention signals early success, but it is success at the lowest peak. In other words, despite achieving product–market fit (PMF), this moment neither is nor should be the ceiling for prediction markets.

0xsmac frames prediction markets as reaching local maxima due to early success, a phrase which I will deliberately overuse in this article to underline that this is not an isolated observation but a confirmation to Smac’s observation.

When we talk about unicorn outcomes, the product–market fit (PMF) status of a product cannot be separated and is mostly determined by timing/market discovery, and the attainment of critical mass. The latter is often the most deceptive. Apparent critical mass at a local maxima can be misread as terminal PMF of a product. Many early products, such as Nokia, being a canonical example, had already reached what looked like dominance, yet were merely sitting at a local maxima that went unrecognized as such.

This is the position Polymarket and Kalshi appear to occupy today. Critical mass, in this context, is not binary. It can be real, or it can be illusory, and distinguishing between the two is what determines whether a market compounds or stalls.

Critical mass can be false and misread (most especially) when:

There are zero to low effort competitors.

Fallacious metrics are used to quantify a product’s success.

I’d like to think that the first point is quite clear, so I’ll bounce to the second.

Just like I did at the start of this article, using notional volume is disgustingly wrong because these metrics can be gamed, and aside from the factor of being able to be gamed, buying and selling can be atomized to raise the notional volume.

By “atomized”, I mean something simple and mechanical: repeated buy–sell sequences, executed back and forth, can manufacture the appearance of activity without introducing any real liquidity or risk transfer

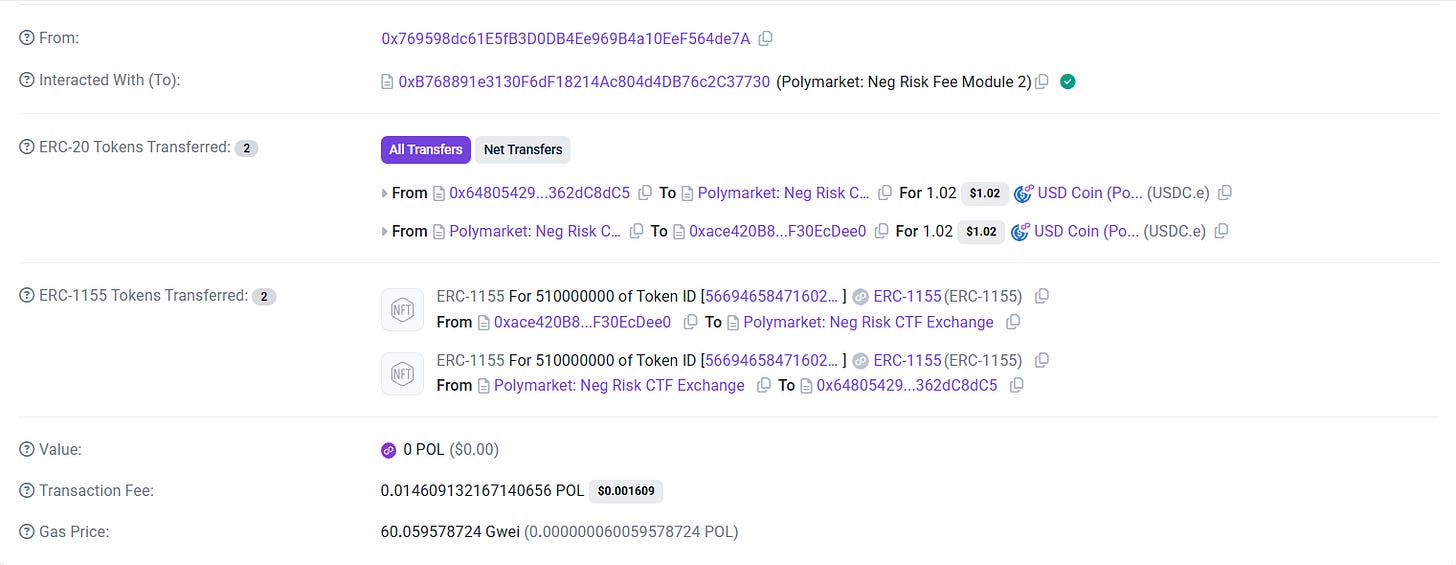

Just as Jez highlighted here, a more practical way to confirm this is from this transaction observed by DataDash:

Polymarket reports 1 share bought, which could be for 0.1 cent as $1, and not the actual volume which was traded, which clearly demonstrates how notional volume as a metric can be inflated. Just as shown in the screenshot, 510 shares were purchased for only $1, but this will be recorded as $510 in notional volume instead of $1.

Polymarket and Kalshi are currently overvalued due to similar deceptive metrics and a misinterpreted critical mass.

This local maxima leads to the deception, but in the moment, I can hear you scream out loud questions: “How about the adoption, is there any other prediction market that can stand the chance?” I hear you, but since this article points out where prediction markets stand, this doesn’t cancel out its attainment of PMF. Of course, it introduces a new asset class, hence its chances of staying are quite certain, but the question of whether it will ever leave local maxima remains, and I am laying my arguments about what’s needed to surpass this “local maxima.”

Dependencies to remain in this local maxima are due to:

Insufficient liquidity.

Impartial component to compete with traditional sportsbooks.

Inability to square in all possible factors.

1. Insufficient Liquidity

I think of prediction markets as a distinct asset class, primarily because of how fundamentally different their trading mechanics are from prior financial innovations. Historically, innovations tend to persist when they introduce not just new instruments, but entirely new asset classes. Markets are always searching for novel things to trade and novel ways to trade them; in that sense, trading real-world events is no longer speculative or hypothetical. Like any emerging asset class, prediction markets require capital rotation and sustained inflows to mature.

This is where the core power players of any asset class, exchanges, market makers, and liquidity providers become unavoidable. Regardless of the externalities they introduce, liquidity cannot be discussed seriously without accounting for these participants. Asset classes are not defined solely by ideology or novelty, but they are shaped by the actors who enable price discovery at scale.

One might ask: Is liquidity really the problem? Don’t limit orders; simply update over time? That reasoning is understandable, but incomplete.

If liquidity were not a constraint, the last traded price would not play such an outsized role in determining an asset’s perceived value, just as it is in Polymarket, because liquidity, or the lack of it, governs how prices form and how meaningfully markets can be traded.

Placing a $2 price can move the price of YES shares from 66 cents to 68 cents, but in spot order books, $2 deposit feels like trying to poke an elephant’s legs with the thumbs of a baby.

If a token with a $2B FDV can see its price collapse from a single $150k short, does that mean that the token is actually worth $2B FDV?

The same dynamic becomes clearer when you look at multi-outcome markets on Polymarket. Each outcome “yes” or “no” has its own order book, yet both are ultimately collateralized to settle at $1. Until resolution, these shares are independent instruments for price discovery, even though they are economically linked at expiry.

When a share’s price is primarily determined by the size and direction of the most recent trade, that is a liquidity signal (either a sign of sufficiency or lack), not a valuation signal. And while Polymarket incentivizes tighter spreads through trader incentives, this mechanism does not replace the structural role of market makers. Spread discipline alone cannot manufacture depth.

For market makers reading this, pricing a share becomes a function of domain-specific expertise.

Each market category relies on different data inputs and behavioral patterns. Inasmuch as correlations across categories exist, they are event-inconsistent, which makes generalized pricing models fragile without sufficient liquidity and participation.

A $2,000 trade should not be capable of materially repricing a market. Yet when it can, it reveals the absence of a coherent pricing framework.

Without stable price formation, larger institutions remain sidelined. This environment benefits retail participants and smaller traders in the short term, but the resulting volatility and short-horizon thinking obscure the longer-term potential of prediction markets beyond local maxima.

Market making itself has even evolved from what it used to be. The shift from “3.0” to “4.0” reflects a move away from relying on price dislocations and toward strategies centered on funding rates, open interest, and positioning. High open interest may serve as an experimental entry point for market makers in prediction markets, but whether this becomes sustainably profitable remains an open question.

Kalshi even offers a revealing case study. Its disclosures indirectly highlighted how unprofitable internal market making can be. Despite the apparent advantage of operating with fewer competitors, the economics have not played out as expected, which shouldn’t be the case. Being early should offer an upside at least.

2. Impartial component to compete with traditional sportsbooks.

The propensity for two bodies to move is determined by the components that constitute them. In some cases, those bodies are not even built from comparable parts. This distinction matters. In the vertical where on-chain prediction markets operate, this structural difference is precisely where success has emerged. The same logic applies to traditional sportsbooks. Polymarket, however, does not currently compete with sportsbooks, not because it cannot, but because it does not need to. The two operate in adjacent but fundamentally different industries. That said, this separation may only hold until local maxima are fully explored, for a stronger and visible competition.

For prediction markets to compete directly with sportsbooks, additional primitives are required, of which the most important of them all is parlays. Traditional sportsbooks/platforms are a lot more sticky due to this single feature. Kalshi has introduced parlays, though jurisdictional constraints prevent me from testing them firsthand. Polymarket, by contrast, warrants direct criticism for its parlay design choices.

Polymarket inherently has faced the core issue and bottleneck of event resolution due to its reliance on the UMA oracle. The most popular of all cases was in the Zelenskyy suit market.

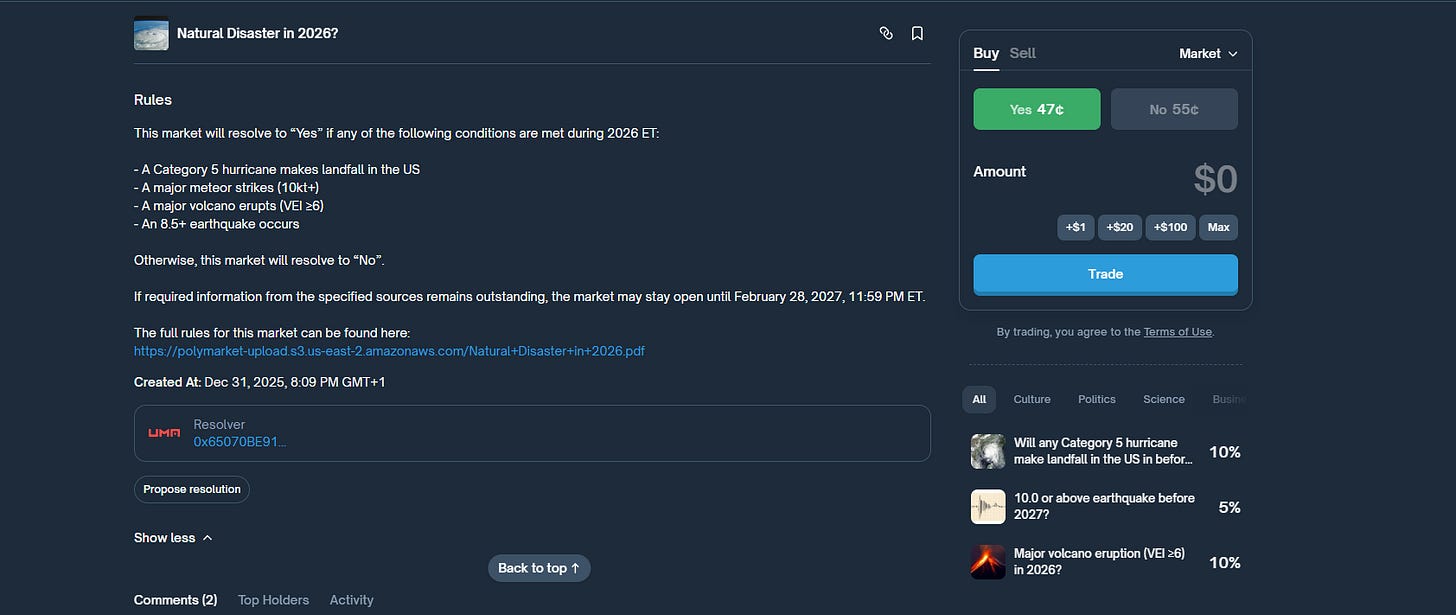

This is an example of a market with parlays, where you can bet that a natural disaster will happen in 2026, but this parlay, atypical of traditional sportsbooks, is conditional and not based on stacking. Traditional sportsbooks make it possible for users to stack different games; hence, the condition to gain rewards is dependent on the stacks of games and not on wide differences and possible scenarios that could make my prediction fail. In this same vein, proposals of resolutions will amass when 1 out of 3 conditionals are stated to be true despite their falsity.

3. Inability to Square in all the Factors:

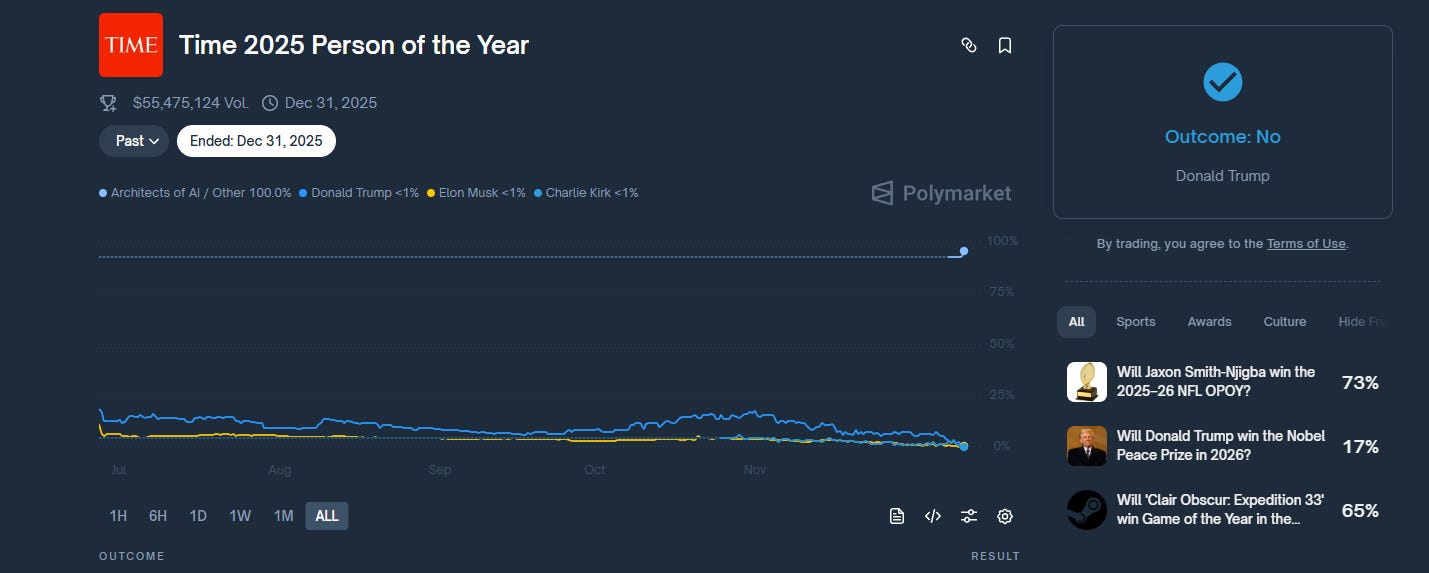

Predicting real-life possible occurrences proves to be a hassle on Polymarket, as seen in an exemplary past market “Time 2025 Person Of The Year”, the following outcomes were present, as shown in the image:

Time Person Of The Year was given to “Architects of AI,” and lots of individuals expected Artificial intelligence to be collateralized for the $1, but “other” got the resolve which stirred up so many arguments, and this has higher chances of occuring again till Polymarket can have a way to make every outcome not generic just like how Artificial intelligence was included. For this, I believe running synthetic data for outcomes will solve this hitch greatly.

Tulip also suggests a better model here for Polymarket to expand beyond the local maxima. In the meantime, have fun on prediction markets and be aware that the local maxima will be relatively lower than what you/we see now.

To sign off, I’d love to mention that the integration of Polymarket and Kalshi into superapps is seen as a vast distribution, but still inclusive of what makes the local maxima hard to sense.

I have been looking into Polymarket, Opinion. XO Market, and trying out platforms like Polycule and Fireplace. If you’d like to trade on Polycule, you can start here with my referral link. Fireplace is also a good tool to try out, but for now, my invites are exhausted. If you’d love to try out the platform, you can send me a DM here on X or Telegram, and I’ll help you right away.

Beautiful read man!

Personally, I think it's a long ways until prediction markets (polymarket/Kalshi) can compete or stand toe-to-toe with them – primarily because of the kind of asset class prediction market shares are (parlays generate the most revenue for betting gambling platforms since people naturally prefer higher odds and outsized returns) and how their markets are resolved.

Currently, I think any competition in that niche will have to outdo Polymarket and Kalshi on those two fronts (especially if one can excellently implement parlays)

So on the issue of local Maxima for Polymarket and Kalshi, I think it's a race to see who evolves better faster.

That'd create a monopolistic gap (which will take time to close)

good stuff dude!